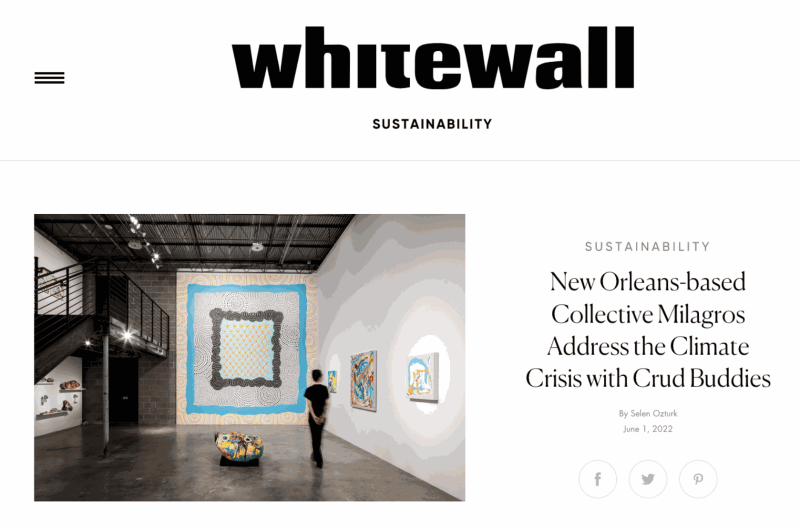

Milagros is a collective led by Latinx artists Felici Asteinza and Joey Fillastre. Their recent exhibition, “Saturater,” was on view at Ten Nineteen Gallery in New Orleans last month, featuring small sculptures, named "Crud Buddies," made from discarded styrofoam found along the banks of the Mississippi River and shaped by rolling water over time. Milagros paints and embellishes the objects with brightly-colored resin, rhinestones, and handmade ceramic facial features, giving each a name and personality. These anthropomorphized found-object pieces are developed in collaboration with Healthy Gulf (an organization committed to the ecological restoration of the Gulf of Mexico) and confront ecological excess and destruction through a respectful, resilient, and inclusive visual language.

Whitewall spoke with Milagros about the beginnings of “Crud Buddies,” artistic influences and previous projects, and the future ahead.

WHITEWALL: “Saturater” maintains a colorful, multi-media aesthetic of your previous work that lends itself particularly well to murals! Did the collective start off making murals, or develop the idea from previous projects?

FELICI ASTEINZA: It definitely developed over time. It started in Gainesville, FL, when we took over the space of a former baptist church slated for demolition. It was a place for us to experiment, to paint collaboratively, to bring people into our work, and see what could happen inside of it. At some point, we started to paint entire rooms. This led to public art and then, eventually, to murals.

JOE FILLASTRE: We’ve always been maximalists. Eventually, we outgrew the frame and started thinking about what it would mean to apply our visual language to other things.

WW: What is the draw of mural and public installation art for you?

JF: It’s the accessibility and potential for immediate impact. With public murals, we create them for connection with the widest possible audience. They’re about community. There’s no barrier to entry. At the same time, though, we’re careful to be very sensitive to our audiences. The ideal is that there is a balance between making something beautiful or engaging and making something that keeps the spirit of place. You want the people living and working in the neighborhood to have a stake in it. For us, this can mean partnering with organizations that are deeply rooted in the community.

WW:The pandemic has seen an increase of public art installations like murals in cities and communities on the local scale. How has this time affected the direction of or thought behind your art practice?

FA: We experienced the opposite, actually. Public art projects that we were involved with lost funding, and we didn’t have any prospects for a long time. We had to change direction entirely, pivoting away from large-scale projects and toward more intimate, smaller-scale works. This is when we really started to focus on Crud Buddies.

JF: Everyone was in isolation. We started to think a lot about discrete, one-on-one interactions and how we could facilitate that with object-based things.

WW: The folk-craft, collaborative-material tradition also very much pervades the work of Milagros. How were each of you introduced to the arts?

FA: My father is Cuban, my mother is Mexican, and growing up there were colors and patterns that reflected the Latino traditions around me. Growing up Catholic, I was drawn to the big stained glass windows, ornate statues, colorful altars, these big-impact moments. My father’s family was also into Pre-Columbian art. My maternal grandmother went to school in Mexico for painting and she always made her own clothes, which is probably where my interest in textiles comes from. And my paternal grandmother was a musician. That being said, my family actively discouraged me from becoming an artist when I went to college.

JF: My maternal grandmother was always quilting. I think from watching her, I developed a deep appreciation for pattern, texture, and the hand-made. I have been making things for as long as I can remember, and my family always encouraged it.

WW: What influenced you to work within and reimagine this artistic tradition specifically?

FA: I think we connect with the way that folk art channels the ideas and values of a community. The accessibility, too. Our goals are similar: how can we facilitate community through art? How can we create together?

JF: It’s also storytelling. Folk art speaks in a way that people hear and understand. The way we add facial features and create personalities, we’re doing something similar—we’re also fascinated with pet rock culture. With folk craft, there’s also this idea that the pieces have a function. We’re kind of flipping this on its head. Think about the life cycle of this foam trash we find on the banks of the Mississippi River. We’re giving an object the ability to tell a story that is very different from its material past.

WW: “Crud Buddies” presents a great contrast with your installation and canvas projects on the level of scale. What would you say are the advantages (and disadvantages) of artistically reckoning with sociopolitical and environmental issues on either the grand or small scale?

JF: The climate crisis is this huge abstract thing. It’s daunting just to think about. Taking the scale down, and making something bright and fun, we’re able to offer a happy entry point to a dark subject. We’re also transforming the foam trash enough, so it’s deceiving in its materiality. So we get questions about what they are right off the bat, and this opens the door for other conversations. The first instinct is not “oh, it’s petrotrash, it’s an existential problem that we face daily” but you can get there.

FA: I think that even on this smaller scale, it’s still about impact—just a different kind of impact, an intimate and personal relationship. These objects are living in people’s homes, on shelves, on coffee tables. The web of conversations over time multiplies quickly, all spurred by one funny-looking object. Individual sales also give us a way to increase awareness and give money. We’re artists. Our best utility in this situation is to be a liaison to the folks with boots on the ground.

WW: What was it like collaborating with Healthy Gulf to develop this project? Do you see future collaborations in the future?

FA: Healthy Gulf is amazing. We were connected with them during our residency at A Studio in the Woods, where we were doing a deep dive into this project. A Studio in the Woods connected us because Healthy Gulf has a history of collaborating with artists in the past. We were looking for ways to directly connect people to resources about the pollution in the Mississippi River and they were interested in partnering with us on this project. They are doing the real work to assist people being impacted by the climate crisis in our region. They’re working deep in Gulf communities, offering tangible help to people directly affected, picking up where other resources leave off, or don’t exist, thinking about a person’s specific needs today as well as strategizing to prevent the future pollution of our waterways. It has been really inspiring to see how they work.

WW: What are you working on next? What projects are you envisioning?WW: What are you working on next? What projects are you envisioning?

JF: We have an installation at MoCA Jacksonville coming up in December and some mural work coming up in Miami that hasn’t been announced yet. We’ll continue to work on our Crud Buddies, maybe evolving it into something new. We’re cautiously optimistic about the future.